Elliptic operator

In the theory of partial differential equations, elliptic operators are differential operators that generalize the Laplace operator. They are defined by the condition that the coefficients of the highest-order derivatives be positive, which implies the key property that the principal symbol is invertible, or equivalently that there are no real characteristic directions.

Elliptic operators are typical of potential theory, and they appear frequently in electrostatics and continuum mechanics. Elliptic regularity implies that their solutions tend to be smooth functions (if the coefficients in the operator are smooth). Steady-state solutions to hyperbolic and parabolic equations generally solve elliptic equations.

Contents |

Definitions

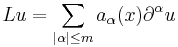

A linear differential operator L of order m on a domain  in Rd given by

in Rd given by

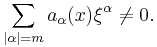

is called elliptic if for every x in  and every non-zero

and every non-zero  in Rd,

in Rd,

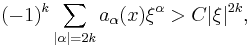

In many applications, this condition is not strong enough, and instead a uniform ellipticity condition may be imposed for operators of degree m = 2k:

where C is a positive constant. Note that ellipticity only depends on the highest-order terms.

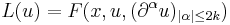

A nonlinear operator

is elliptic if its first-order Taylor expansion with respect to u and its derivatives about any point is a linear elliptic operator.

- Example

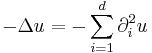

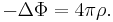

- The negative of the Laplacian in Rd given by

- is a uniformly elliptic operator. The Laplace operator occurs frequently in electrostatics. If ρ is the charge density within some region Ω, the potential Φ must satisfy the equation

- Another example

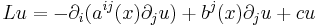

- Given a matrix-valued function A(x) which is symmetric and positive definite for every x, having components aij, the operator

- is elliptic. This is the most general form of a second-order linear elliptic differential operator. The Laplace operator is obtained by taking A = I. These operators also occur in electrostatics in polarized media.

- Yet another example

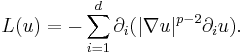

- For p a non-negative number, the p-Laplacian is a nonlinear elliptic operator defined by

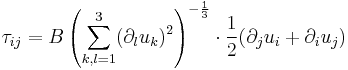

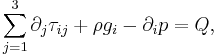

- A similar nonlinear operator occurs in glacier mechanics. The stress tensor of ice, according to Glen's flow law, is given by

- for some constant B. The velocity of an ice sheet in steady state will then solve the nonlinear elliptic system

- where ρ is the ice density, g is the gravitational acceleration vector, p is the pressure and Q is a forcing term.

Elliptic regularity theorem

Let L be an elliptic operator of order 2k with coefficients having 2k continuous derivatives. The Dirichlet problem for L is to find a function u, given a function f and some appropriate boundary values, such that Lu = f and such that u has the appropriate boundary values and normal derivatives. The existence theory for elliptic operators, using Gårding's inequality and the Lax–Milgram lemma, only guarantees that a weak solution u exists in the Sobolev space Hk.

This situation is ultimately unsatisfactory, as the weak solution u might not have enough derivatives for the expression Lu to even make sense.

The elliptic regularity theorem guarantees that, provided f is square-integrable, u will in fact have 2k square-integrable weak derivatives. In particular, if f is infinitely-often differentiable, then so is u.

Any differential operator exhibiting this property is called a hypoelliptic operator; thus, every elliptic operator is hypoelliptic. The property also means that every fundamental solution of an elliptic operator is infinitely differentiable in any neighborhood not containing 0.

As an application, suppose a function  satisfies the Cauchy-Riemann equations. Since the Cauchy-Riemann equations form an elliptic operator, it follows that

satisfies the Cauchy-Riemann equations. Since the Cauchy-Riemann equations form an elliptic operator, it follows that  is smooth.

is smooth.

General definition

Let  be a (possibly nonlinear) differential operator between vector bundles of any rank. Take its principal symbol

be a (possibly nonlinear) differential operator between vector bundles of any rank. Take its principal symbol  with respect to a one-form

with respect to a one-form  . (Basically, what we are doing is replacing the highest order covariant derivatives

. (Basically, what we are doing is replacing the highest order covariant derivatives  by vector fields

by vector fields  .)

.)

We say  is weakly elliptic if

is weakly elliptic if  is a linear isomorphism for every non-zero

is a linear isomorphism for every non-zero  .

.

We say  is (uniformly) strongly elliptic if for some constant

is (uniformly) strongly elliptic if for some constant  ,

,

for all  and all

and all  . It is important to note that the definition of ellipticity in the previous part of the article is strong ellipticity. Here

. It is important to note that the definition of ellipticity in the previous part of the article is strong ellipticity. Here  is an inner product. Notice that the

is an inner product. Notice that the  are covector fields or one-forms, but the

are covector fields or one-forms, but the  are elements of the vector bundle upon which

are elements of the vector bundle upon which  acts.

acts.

The quintessential example of a (strongly) elliptic operator is the Laplacian (or its negative, depending upon convention). It is not hard to see that  needs to be of even order for strong ellipticity to even be an option. Otherwise, just consider plugging in both

needs to be of even order for strong ellipticity to even be an option. Otherwise, just consider plugging in both  and its negative. On the other hand, a weakly elliptic first-order operator, such as the Dirac operator can square to become a strongly elliptic operator, such as the Laplacian. The composition of weakly elliptic operators is weakly elliptic.

and its negative. On the other hand, a weakly elliptic first-order operator, such as the Dirac operator can square to become a strongly elliptic operator, such as the Laplacian. The composition of weakly elliptic operators is weakly elliptic.

Weak ellipticity is nevertheless strong enough for the Fredholm alternative, Schauder estimates, and the Atiyah–Singer index theorem. On the other hand, we need strong ellipticity for the maximum principle, and to guarantee that the eigenvalues are discrete, and their only limit point is infinity.

See also

- Hopf maximum principle

- Elliptic complex

- Hyperbolic partial differential equation

- Ultrahyperbolic wave equation

- Parabolic partial differential equation

- Semi-elliptic operator

- Weyl's lemma

References

- Evans, Lawrence C. (2010) [1998], Partial differential equations, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, 19 (2nd ed.), Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-4974-3, MR2597943, http://www.ams.org/bull/2000-37-03/.../S0273-0979-00-00868-5.pdf

- Gilbarg, David; Trudinger, Neil S. (1983) [1977], Elliptic partial differential equations of second order, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften, 224 (2nd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-13025-3, MR737190, http://www.springer.com/mathematics/dyn.+systems/book/978-3-540-41160-4

- Shubin, M. A. (2001), "Elliptic operator", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=Elliptic_operator

External links

- Linear Elliptic Equations at EqWorld: The World of Mathematical Equations.

- Nonlinear Elliptic Equations at EqWorld: The World of Mathematical Equations.

,v) \geq c\|v\|^2](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/1775a90f3340805cdbd2a982311970dc.png)